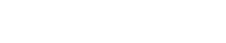

Exploring the brilliant techniques Bowie used to populate his Major Tom saga

In my songwriting classes, I assign a week where the students are to write a “story song” — a piece of music with a character that develops and takes us on a journey of some sort. The students generally look at me cross-eyed. Once, upon hearing the assignment, a student asked, “You mean, like…Meatloaf?” To which another asked, “Who’s Meatloaf?” A third cleared things up by offering, “No, he means kinda like ‘Stan,’” referring to the Eminem song from their distant collective childhoods.

Yes. Like “Stan.”

At the moment, songs — and I’m generalizing, though popular charts do bear this out — tend to hone in on a particular moment and expand upon a fixed sensation. For instance, Adele’s “Hello,” the most popular song at the time of this writing, pushes out from a personal phone call to reveal her anguish over a past relationship. Songs with a wider lens use the first person plural (“we”) and are addressed directly to audience members in hopes of generating a rallying cry — the all-powerful “anthem.” (Fun’s 2011 hit “We Are Young” comes to mind.) EDM and electronic genres sidestep the whole concept of story by either eliminating lyric completely, or relegating a vocal part to a sampled and repeated hook. In this case, the music serves as a personal soundtrack that can be interpreted in ways that are not limited by language. Its inherent vagueness allows it to scale as others fill it with meaning, as if it were the audio version of Facebook.

None of this is new to music, of course, and I don’t draw sociological conclusions about my students or their “generation” the way some have. My goal in class is to identify a song that’s working well or could work better. As to the techniques my students use, well: pop music is fashion, and the power to charm. Hemlines go up, hemlines go down. Who knew that better than David Bowie?

***

Here am I floating in a tin can

Far above the world

Planet Earth is blue

And there’s nothing I can do

I must have been 11 or so — younger, even? — when I first heard “Space Oddity.” It was after soccer practice, and I was in an oversized bathtub with high porcelain walls that I pulled myself up on to stare at the nearby clock radio. I remember feeling as though music had stopped coming out of it, and instead a film had begun unspooling onto the tile floor by my cleats and jersey while images projected onto some new and unknown screen in the middle distance. More than the music, or the playing, or the vocal prowess, I was transfixed by the story of Major Tom’s space voyage, and rapped my fingers impatiently on the tub during the guitar solo as if to say stop noodling and get on with it…WHAT HAPPENS TO MAJOR TOM!?

As with all great stories, you only get one chance to be as shocked as I was with the outcome, but thinking about it now, I can piece together some of the techniques Bowie used to populate the song so brilliantly. I wonder if I can inspire some of my students to give story songs a new look, not out of nostalgia, or because I think they’re writing less compelling music now, but simply because a great story has incredible power.

***

Ground Control to Major Tom

A bane of story songwriting is dialogue between two characters — because you can’t sing quotation marks or line spaces, you have to spend valuable time reminding the listener, “He said_____”/”She said_____,” etc. With notable exceptions (The Beatles’ “She Said She Said” comes to mind), it’s busywork to keep a story straight.

By simulating two-way radio conversation, Bowie not only makes that busywork a story-enriching detail, but he keeps the characters perfectly aligned in the process. He starts each verse with this same device, and by the end of the song, it’s become a refrain in itself — a “hook,” in pop music terminology. As a result, it’s one of the most recognizable opening lines in pop music.

Commencing countdown, engines on

The overdubbed countdown to launch serves a dual purpose, in that it’s a critical part of the story, but it’s also a classic device: the use of sequence. From the Jackson 5’s “A, B, C,” to Feist’s “1 2 3 4,” songwriters are always looking for sequences that pull already ingrained knowledge into the new context of the song. For Bowie, the sequence was sitting there, and by using it in the background of his refrains instead of calling full attention to it, he’s overlaying two hooks that are effortlessly through-composed within the story.

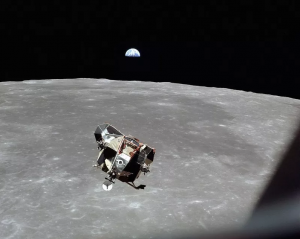

The blast-off: The instrumental depiction of the rocket launch is, to me, one of the great moments in pop art. It marries chaos, ambition, storyline, the popular fascination with space travel, and the expanding limits of what a rock band can do. I can only imagine what Andy Warhol must have been thinking the first time he heard it. But instead of falling into gratuitous self-indulgence, all of the ideas hold together, thanks to the precise narrative Bowie has established. The story allows it, just as it allows the triumphant resolution and the hilariously crass congratulations of Ground Control:

And the papers want to know whose shirts you wear

His quick slap at consumer culture, and his wink to the listener, contextualizes us as part of the ride. How quickly a colossal human feat is reduced to the knuckle-dragging greed of the marketplace — but then, we’ve grown up watching NASCAR drivers guzzling sponsored milk in the winner’s circle, and Olympians touting the virtues of going to Disney World moments after capturing the gold. As weird as he appeared on the surface, Bowie reminds us that he’s one of us — an alien who manages not to alienate.

Here am I floating in a tin can

“Space Oddity” takes two substantial breaths in the writing, which are generally referred to as “bridges” or “B-sections.” Often, these sections give the listener a different angle from which to view the goings-on in the song. Bowie uses them to widen the musical arrangement and provide Tom’s internal monologue. For all the chatter with Ground Control, he’s the one alone up there, with moments to reflect on the scale of our species in face of the universe. As Jodie Foster put it in 1996’s Carl Sagan-inspired film, Contact, “They should have sent a poet.” In “Space Oddity,” Bowie actually did send one.

Tell my wife I love her very much

She knows!

In making Tom a married man, his vulnerability increases immensely, because now love is also hanging by the tenuous threads and crude technology of a young space program. As a listener, we know that, if those threads break, the damage is both irreversible, and personal. Major Tom has a whole other life — a lawn to mow, pictures framed on his mantel, maybe children — that is implied in a single couplet. This is sheer soap-opera drama meant to raise the stakes of the mission, and Bowie, an actor himself, knew its appeal. If present-day songwriters have stopped pushing these kinds of melodramatic buttons, rest assured Hollywood has not: The Power of Love burns at the center of recent Sci-Fi blockbusters The Martian and Interstellar, and the public — to which Bowie played — clearly has not tired of it.

Planet Earth is blue

And there’s nothing I can do

Bowie returns to the philosophical B section as he realizes his mission is doomed, but now the repeated lines have a new, tragic meaning: at first, he is reflecting on how inconsequential he feels against the vast backdrop of the universe; in the second, he admits there is nothing he can do to save himself from being swallowed by it. This is the very definition of song development: having a repeated section that means something new by the time the journey of the song has reached its climax.

The outro: Bowie shows a slight sadistic side by never completing Tom’s fate: instead of giving us a final, resolving chord, the song fades into the void, leaving Major Tom to spin for eternity. His departure lasts for a full minute, or 20% of the entire song, and having empathized with him — the fragile, married man who was nearly a hero — we have no choice but to recognize that, ultimately, his fate is ours.

***

That’s the kind of thing a story song can do, and it’s the reason I put the idea in front of my students, despite current trends of the day. It’s not as if we’ve lost our collective appetite for great characters and archetypal plots, after all. We’re not out of new stories, and we’re not even tired of the old ones, as the Star Wars franchise reminds us on a regular basis. Maybe today’s David Bowies have been lured to other, more innovative and story-friendly forms — Web series, podcasts, video games, and so forth. Maybe our attention spans won’t accommodate yet another plotline in our data-addled days. But somewhere in the pop music ether, the story song might still retain its dormant power, and is waiting out the fashions of the moment. Hemlines are decidedly down. Maybe that means there’s only one way for them to go.

(also on Medium)

Dylan’s, The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll immediately comes to mind as another supreme example of this powerful song form.