by Mike Errico | Oct 14, 2015 | Lessons, Teaching

Thanks to Ben Mink and Michael Beinhorn, brilliant producers who came to my class at NYU’s Clive Davis Institute to discuss their creative roles in the recording process. Michael told us how he had to send Soundgarden home to write more songs, pushing them to a career high with Superunkown. Ben played us traditional klezmer music, which influenced him early on, and drew a direct line to the chorus of kd lang’s hit, “Constant Craving,” which was then co-opted by the Rolling Stones in their song, “Anybody Seen My Baby?” It pained me to tell them we were out of time. Ben Mink http://www.benmink.com Ben Mink’s wide range of recording collaborations includes Feist, k.d. lang, Rush, Alison Krauss, Daniel Lanois, Roy Orbison, Elton John, Heart, the Klezmatics, Wynona Judd, Method Man, and many more. He has been nominated for nine Grammies, winning twice for his work with k.d. lang. In 2007, he was co-nominated for his work on Feist’s 1234, which gained global popularity in the rollout campaign for the iPod Nano. In 2011, the TV series Glee used Ben’s composition “Constant Craving,” performed by Chris Colfer, Idina Menzel and Naya Rivera. Mink has lectured on such topics as “The Music Business vs. the Creative Process,” at the University of British Columbia, Western Washington University and Simon Fraser University. He has also worked with students as an associate of UBC’s Department of Mechanical Engineering (robotics) and is an associate member of the Institute for Computing, Information & Cognitive Systems. Michael Beinhorn http://michaelbeinhorn.com/ Michael Beinhorn’s production has played a primary role in creating career-defining records for artists including Marilyn Manson,...

by Mike Errico | Sep 3, 2015 | Teaching

(I’ll be teaching songwriting at NYU, and speaking about it at Wesleyan and Yale (so far) this semester. Here are some of the things I’ll be trying to get across.) Our classroom is tucked up into the third floor of an elegant red brick building with Ionic columns that make you feel smart even if you’re just looking for a place to nap. Fluorescent bulbs hang high in the ceiling and cold formica tables form a rectangle we’ll barely fit around. I’ve staked out the corner near the A/V controls—the projector, the volume knob on the speakers—but otherwise, the layout seems fairly democratic. It was hard to get into this class. Students sent songs and sketches and emailed pleas with logical reasons why it fit with their majors and how they envisioned their lives. I made cuts based on a 50-word petition and a link to a recording of theirs, hoping in each case that I’ve done the Future some service. They fill the room with stickered-up laptops and water bottles and news of dorm room switches and class cancellations. They pack themselves around the table, more comfortable with each other than I am with my own family at Thanksgiving. I will teach them about songwriting. I have no idea what that means. No one stops me. I don’t actually believe in pop songs, and it’s hindered my career as a songwriter. Pop songwriting is a calling, and though I’m touched by it, I never really got the call. Example: I have a friend, Chris, who saw Jesus walk out of his high school locker. They spoke. Now he’s...

by Mike Errico | Jun 9, 2015 | Teaching, Text Journalism

Honored to have ASCAP pick up my piece on tech’s effect on songwriting. Question: In the streaming economy, do songs have a financial incentive to change what they look and sound like? For instance, Spotify, the clear leader in the streaming space, pays after 30 seconds, so an honest question is: Why write beyond that? And… Are you, in fact, screwing yourself six times over for writing a three-minute song (:30 x 6 = 3:00 song)? A “song disruptor” would just cut everything back to :32 or so, and see huge positive results in his/her own streaming royalty statements. Labels would love it for the same reason (more money). Thinking ahead: If a critical mass were to adopt song forms of these lengths, would Spotify payouts to creators suddenly rise sixfold? That would probably crush the business model, wouldn’t it? I mean, it can’t make a profit as is, and songs are clocking in at around three minutes. Are streaming services just skating by on all that non-monetized listening time? Spotify also pays higher rates at around five minutes — because of course it does. It makes the company money to not have to pay out for four entire minutes of a song. Taking this into account, what is this thing – songwriting – going to look and sound like in the not-too-distant future? Read more on ASCAP’s web site. Original post on...

by Mike Errico | May 26, 2015 | Teaching, Text Journalism

Outside my songwriting classroom at NYU’s Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music, the industry is in full disruption mode. This semester alone, publishers continued to weigh new methods to take back control of their copyrights; a controversial judgment regarding “Blurred Lines” spurred debate on what copyright even is; Congress heard arguments regarding how artists and songwriters are getting paid; Pandora and Spotify and Grooveshark and Rdio all made headlines; Tidal launched (Jay-Z even came to Clive to talk about it); Apple readied a new streaming service… friggin’ Starbucks jumped in, and I’m just going to stop there, because you get the point. At times, I’ve wanted to triple-lock the classroom door for the brief fourteen-week period so we can focus on the art. But that hasn’t been easy, and in our final meeting, I left my students with a series of rhetorical questions, all of which added up to: With all this going on, what is the future of this thing — songwriting — we’ve been talking about all semester? And is it time for a disruptor to change what songs look and sound like? Read on at...

by Mike Errico | Apr 2, 2015 | Stories, Teaching, Text Journalism

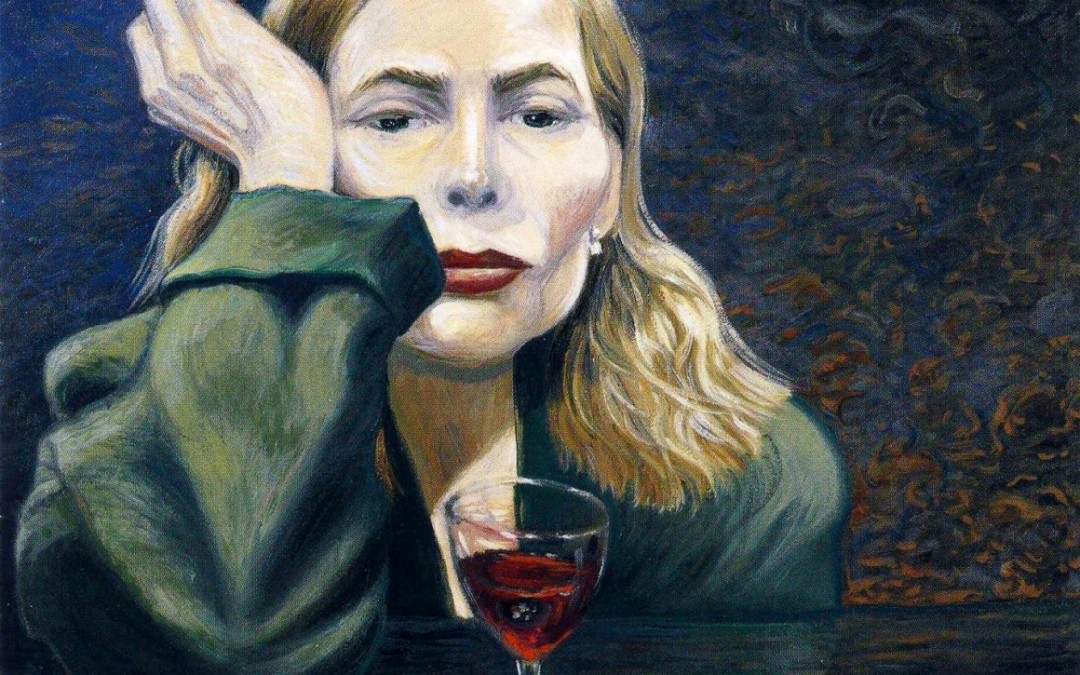

[With attention turning toward Joni’s health, so too has a media shorthand that seeks to encapsulate an artist who has spent her life defying easy classification. But to call her a “60s Folksinger” is to ignore almost everything she’s done. New piece on CUEPOINT.] “If one more major media outlet refers to Joni Mitchell as a “60s Folksinger,” I am seriously going to lose. It.” — Julian Fleisher, via Facebook It took a second for me to register what my Facebook/actual friend had noticed — news outlets using shorthand to encapsulate someone who spent a life defying exactly that. I’m going to suppose that, to some extent, it can’t be helped, that people just don’t have enough time to see more than the easiest talking point. They have careers, lives, and a newsfeed that scrolls endlessly in both directions. “‘60s folksinger” is good enough for enough people. It’s all that people who don’t really care have time to care about. And in an age where the “power” of the sharing economy lies with the consumer and not the artist, perhaps Joni should count herself lucky to be remembered even for that one sliver of her output. But man, I wouldn’t say that to her face. She has been cantankerous with her legacy, scrapping biopics that smell shallow or expedient, eschewing stars who can’t yet hold a candle to the role they’re being lined up to play. Maybe some people are surprised by that — surely she knows the money she’s leaving on the table, right? The sales bump, the retrospectives and accolades she could fill her closets with? Read “Joni Mitchell is Not a ’60s...

by Mike Errico | Apr 1, 2015 | Stories, Teaching, Text Journalism

With a head full of stones and a heart full of sand, I have returned from the Highland Park Record Club. The goal of this gathering was to establish that music and whisky are good friends, maybe even cousins: They both have dynamic personalities that unfold over time; they both are hard to do well; and both warrant repeat drink-listens. We were curated from the creative class and dispatched to a members-only basement where bookshelves swelled with thick hardcovers recounting retrospectives at the Whitney Museum. There were dark, overstuffed couches, and a gas fireplace with a thick glass pane in front of it that offered the dance of light with none of the extraneous by-product of actual fire. There were bowls of nuts with honey notes that whispered from the back of my palette, “How did you get invited here? You’re a fraud.” But I’m not a fraud, I whispered back to my nuts, within earshot of a vinyl technician who scratched garage rock into Plexiglas 45s on a vintage lathe. I am an aficionado, in that I have awakened next to empty bottles of Highland Park and hit play on recording equipment to hear a song that I couldn’t remember I even recorded. So. I’m a pro at this. It’s really something, to hear a song for the first time and know it’s you singing. It’s as close as I may get to inhabiting Keith Richard’s body. Scotch people, I report the following: Highland Park 12 remains a standard bearer, the one you’d hand the Olympic torch and let run down your gullet with trust, even pride; Highland...